🎪 Wonderland Amusement Park opened 120 years ago today

A detailed look at the 10-acre destination for high-tech merriment that once stood at 31st and Lake.

Note: This article is free for everyone. To access everything else, become a subscriber.

The morning of May 27, 1905, brought gorgeous spring weather to Minneapolis. It was a welcome relief after a rainy week, which threatened not just to cramp people's Memorial Day weekend plans, but also nearly delayed one of the most hotly-anticipated events in the young city's history: Opening day at the Wonderland Amusement Park, a high-tech destination for merriment situated on the southern outskirts of the rapidly expanding city.

At 31st and Lake, to be exact.

The opening of the state's first amusement park would draw hundreds of thousands in its opening days and keep the new Lake Street streetcar line swamped all summer. It was yet another feather in the cap of a city that felt itself ascending from a sleepy frontier town to a regional economic power and, increasingly, a proper city with many of the quality-of-life trappings of its larger and older peers. And though Wonderland was ultimately short-lived and left but one building behind, it permanently shaped the trajectory of the neighborhood that would soon grow up around it.

Background

Longfellow in 1904 was essentially a rural exurb. Most homes and businesses were clustered around Lake and Minnehaha, built before the economic panic of 1893 halted new construction for a decade. Lake Street was muddy, rutted, and not connected to public transit. Some of the interior blocks had been platted but only a few scattered homes had been built. Cows outnumbered people on many blocks.

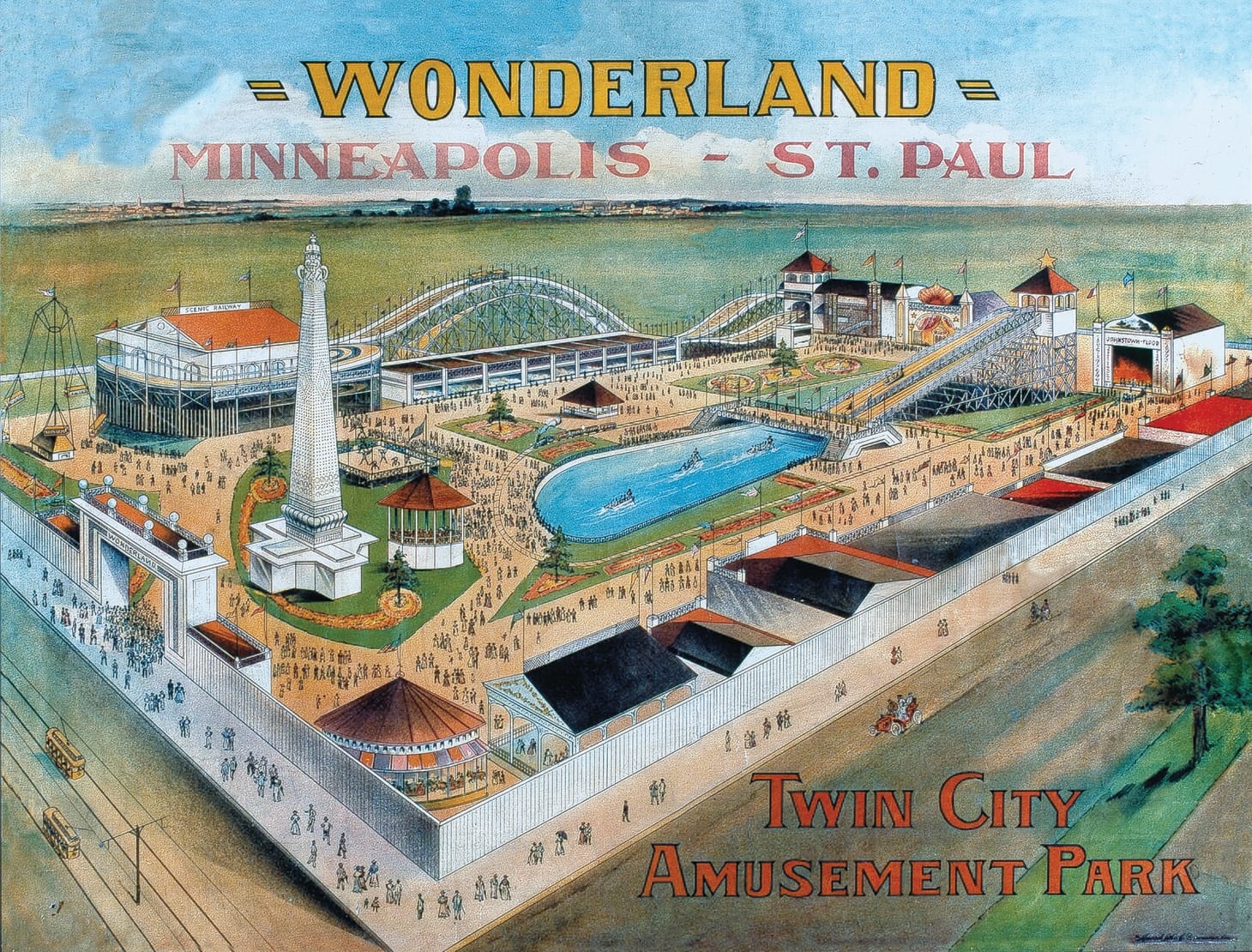

That's what Richard Kann and H.A. Dorsey saw when they scoped out the 10-acre plot of wide-open prairie between Lake Street and 32nd Street, from 31st to 33rd Avenues. The East Coast duo had capitalized on a national amusement park craze that followed the opening of New York's Coney Island, and were looking to build on the success of their park in Connecticut with a few new locations in the Midwest. They saw Minneapolis's booming population and growing middle class as a promising setting for a new park.

It was good timing, as the area was on the precipice of a wave of building that would transform the neighborhood over the next 20 years. Much of that was catalyzed by a planned "Crosstown" streetcar line along Lake Street, which would connect the neighborhood to the all-important streetcar system and would eventually contribute to the development of the bustling commercial hub at 27th and Lake. Between that new line and the older Minnehaha streetcar line that ran to Minnehaha Falls, the rural site would soon be reachable by a majority of the city's residents within a 15-minute ride.

They broke ground in October 1904 with the ambitious goal of finishing the park, with its dozens of rides and 23 buildings, by the following Memorial Day. First up was building a 10-foot wooden fence around the perimeter and digging a lake into the prairie that the log flume would eventually splash into.

Builders worked through the winter as interest built to a fever pitch. In mid-May, the park opened its doors for a three-hour preview, and 10,000 people trudged through the mud to have a look. Streetcar officials prepared their system to handle “as large crowds as have been gathered on any public occasion in either the history of Minneapolis or St. Paul.”

It came down to the wire, but the park was able to open as scheduled, hiring a rash of new workers in the final weeks to battle the rain and complete a minimum-viable park in time for opening day. The city rushed to lay sidewalks from Minnehaha to the entrance of the park, and the much-anticipated Lake Street streetcar opened the same day. ("Chickens fluttering from the track and yelping dogs in pursuit showed that something new was doing on Lake Street," the Journal wrote, poking at the rural nature of the yet-unpaved Lake Street.)

70,000 people showed up for opening day, and 60,000 the next day, even though a majority of the attractions weren't yet ready. By the end of summer, it was all up and running, and a half-million people had paid their 10 cents to walk through the gates — about the population of Minneapolis and St. Paul combined.

"The throng was simply immense," the Minneapolis Tribune wrote, describing one of the park's early days. "Wonderland's ten acres of ground, surveyed from the many points of vantage from which it can be viewed, was literally black with a merry, moving crowd. Outside, the streets were filled with street cars, automobiles, carriages, buses and bicycles, and a wistfully gazing crowd."

The park

Like most American amusement parks, Wonderland was closely modeled after Coney Island. It was touted as an outlet for clean and wholesome fun, an alternative to taverns for a culture growing increasingly weary of alcohol and vice. “Wonderland is calculated to drive dull care away by furnishing innocent recreations which for the moment stir the blood, delight the eye, and cause laughter, practically making people of all ages children again for the hour,” the Tribune wrote in the characteristically wide-eyed manner the park was usually described.

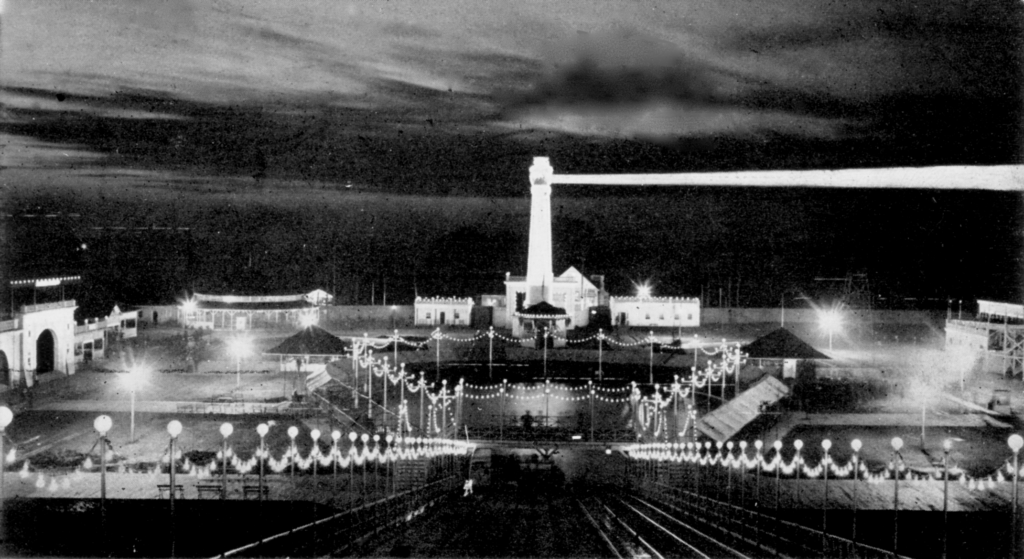

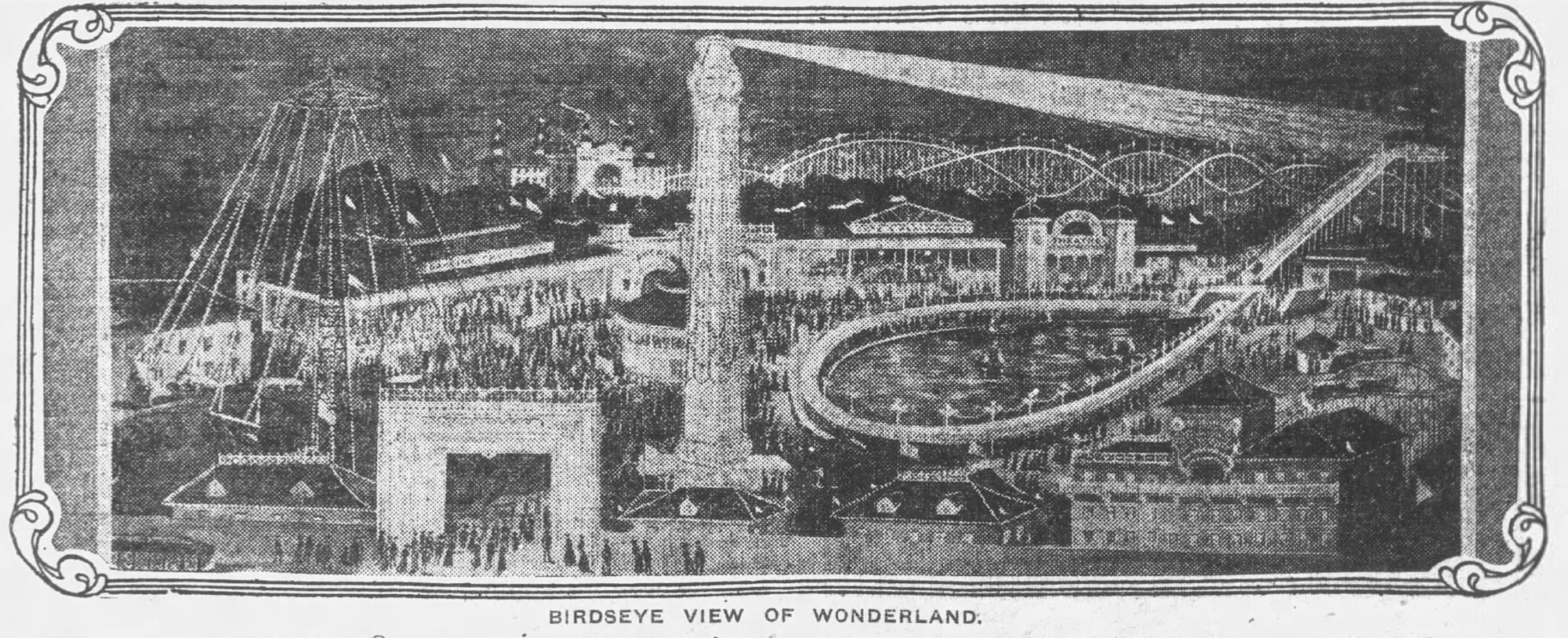

Its centerpiece was a 120-foot tower that used 7,000 bulbs to blare beams of light over the prairies of south Minneapolis, making the nighttime grounds "as light as day" and visible from five miles around. Electric light itself was still a novelty in a city mostly lit by gas lamps. "At night the greatest of all magicians, electricity, will be called upon to add to the beauty and mystery of the place," the Journal wrote. Patrons were allowed to climb the tower and a few even got married on top.

The most enduringly notable feature was the "Infantorium," which used the newfangled technology of incubators to keep premature babies alive. In a strange meld of humanitarian healthcare and crass show business, the care was provided for free, subsidized by the admission fees paid by gawkers, amazed by the fragile babies inside the temperature-controlled glass and chrome boxes. Wet nurses were brought in from Europe and lived upstairs.

Coverage at the time reported that 85 percent of the babies in the facility survived — unprecedented results at a time when few premature babies lived more than a few days — and the 11 that didn't are buried at the Pioneers and Soldiers Cemetery at Lake and Cedar. The design of the pods, which kept a steady temperature and circulated constant fresh air, was not dramatically different from what's used in neonatal wards today.

The biggest thrills came from the "scenic railway" roller coaster, which reached heights of 50 feet and speeds of 40 miles per hour as it rushed riders through tunnels painted as natural caves. In the center of the park, a log flume ride called "Shoot the Chutes" conveyed people up a 50-foot, intensely-lit incline and then plunged them down into a 225-foot-long lagoon.

Beyond those were a slew of attractions that sound, frankly, fun as hell:

- An "Old Mill" underground boat ride through darkened tunnels painted with dramatic scenes

- A 100-foot-high "airship" aerial swing, which was advertised as simulating what it probably felt like to fly in an airplane (the first of which had been flown by the Wright Brothers just 18 months earlier)

- A "Fairy Theater" where viewers wore special glasses that distorted the size of the performers

- A "House of Nonsense" fun house, crystal maze, haunted house, and fortune teller

- Recurring performers like stuntwoman Miss Marie Vokes, who jumped a 35-foot gap on her bicycle, and the Willars Family, who rode unicycles on slack ropes while doing their comedy routine

- Music from multiple orchestras throughout the park, a dance pavilion, and fireworks every night

Closure and redevelopment

After a few salad years, fortunes began to turn at the park. Unusually cold and rainy summers in 1910 and 1911 tanked attendance, and the park began losing money. Losses looked even more likely the next season, as the city announced its plan to finally pave Lake Street in 1912, which would disrupt summer streetcar service.

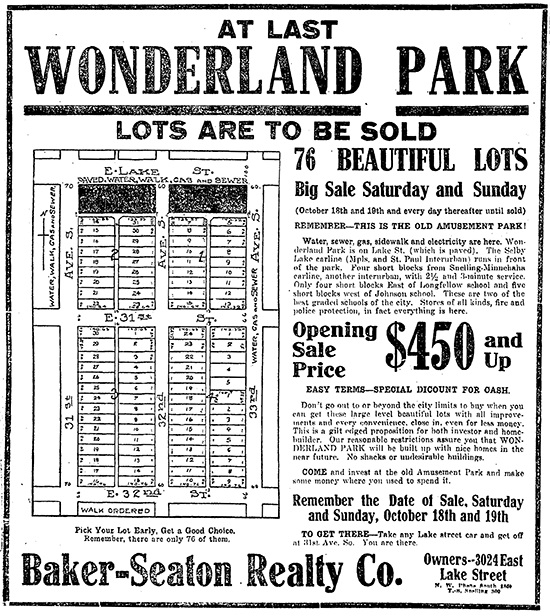

Meanwhile, the land that had been considered the outskirts of the city when they bought it in 1904 had appreciated handsomely. Some of that was driven by the park itself, which "established a familiarity with the region for the general public that has made the broad prairie between that and the river seem less distant and more occupable," the Journal wrote. Wonderland's property had quadrupled in value in the seven years since it opened.

With all that in mind, the duo decided to close the park after its 1911 season and cash in the land for redevelopment.

The park was disassembled and the land went up for sale in 1913. Over the next decade the blocks filled in with many of the homes that still stand today, in an area officially called the "Wonderland Park Addition." The Infantorium remains as an apartment building at 31st and 31st, the only surviving remnant of the park.

Several rides were reportedly rebuilt at Excelsior Amusement Park, which opened in 1925 on Lake Minnetonka, and the aerial swing ride ended up at Antlers Park in Lakeville. Seventy years after Wonderland, Valleyfair would open on the new exurban edge of the encroaching city, serving the same time-tested impulse for clean fun in the presence of others. "The getting together of many people, all intent on enjoyment, in itself is a fascination," the Minneapolis Daily Times wrote at the time of Wonderland's opening. "To even watch others having fun is to very many a keen pleasure."

Lake Street Lift spotlight: Shine a Light on Mama Parade

Join us for the very first “Mama Parade”—a vibrant, one-mile walk that celebrates and honors the essential contributions of mothers and caregivers in our communities. This parade is a tribute to the women who deliver our society, every day, in every way. Hosted by S.H.A.K.E., a Black and women-owned coworking and event space at the Historic Coliseum, and Bus Stop Mamas, a woman-founded company connecting parents to flexible, family-first jobs.

Ad series featuring Lake Street businesses presented by Lake Street Lift